In this month's installment of Field Notes Scott Bowe of Kemp Station discusses Lichens in Wisconsin’s forests, a fascinating organism commonly overlooked.

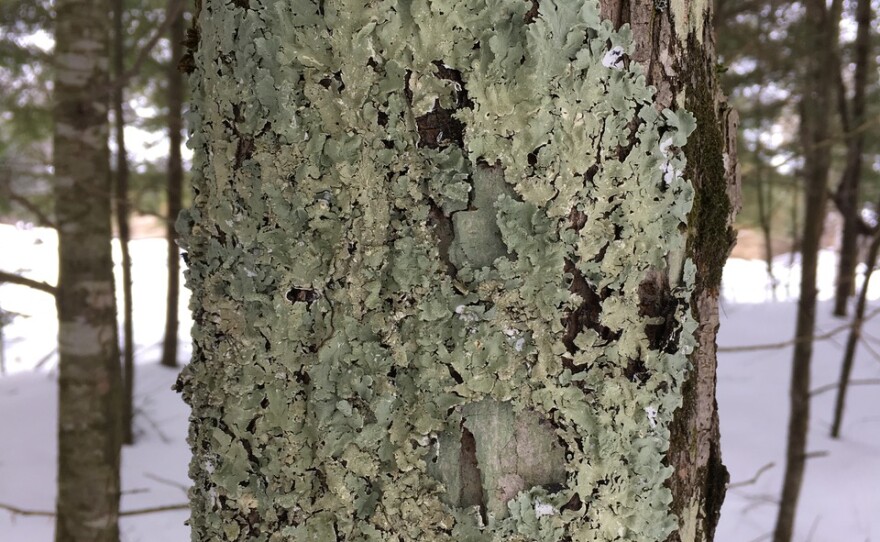

There are many things in our environment that we don’t really see. It’s not that we are ignoring them on purpose, but they just blur into the background. If you are driving, you will pass dozens of utility poles without a second glance, they are part of the background. A group of fascinating organisms that fall into this same background blur are called lichens. In the Northwoods, you will find them on almost every tree and bolder. You will even find them growing on your house roof and siding. From my window, I can see many lichen examples that range in color from green to white and range in size from a pea to a basketball.

What are lichens? They are not animals, even though the ones on trees may have bark! And, they don’t fit into the traditional definition of a plant. Lichens are a symbiotic combination of two or sometimes three organisms: a fungus and a photosynthetic algae and/or cyanobacteria. Symbiotic means that the relationship is beneficial to each of the organisms working together. When you hear the word fungus, you may think of the decay fungus rotting your back porch. That is certainly not a symbiotic relationship. The fungus may be getting the food it needs from the wood, but the porch is getting the short end of that relationship. Lichens get their nutrients from the air and rain. Lichens growing on trees are only using the tree for a growing platform; they are not consuming the tree for food. This makes sense because the same species of lichen could be growing on a rock with no food to offer.

If we look at a lichen comprised of fungi and photosynthetic algae, what does each bring to the relationship? The photosynthetic algae bring the food. Since they are photosynthetic, they take light energy from the sun and convert it into chemical energy in the form of carbohydrates and sugars. The process begins with rain water from the sky, carbon dioxide from the air, and light energy from the sun. It is the same photosynthetic process that trees and plants use. The fungi bring the growing infrastructure to contain and support the algae. In return, the fungi receive carbohydrates and sugars produced by the algae. In addition to the primary symbiotic relationship between the fungi and algae, a lichen or groups of lichens form tiny ecosystems with many other organisms benefiting and forming a complex composite organism.

Lichens grow in several shapes and sizes. Some have tiny, leafless branches called a fruticose form. I think these often look like tiny tumble weeds. Others have flat leaf-like structures called foliose form, and some grow flat on the surface peeling like paint called crustose form. Since lichens do not have roots like plants, they have evolved to tolerate irregular or extended periods without water.

I may only see green and white examples from my office window, but lichens come in may colors including greens, blues, whites, oranges, and yellows to name a few. It is estimated that lichens cover 6% of Earth's land surface. There are about 20,000 known species of lichens world-wide growing from hot dry deserts, to temperate regions like Wisconsin, to the arctic tundra. Many of you may have seen photos of reindeer eating “Reindeer Moss” in the arctic. Reindeer Moss is not a moss but a lichen.

Lichens are a pioneer species. Just like aspen trees may be the first tree species to establish after a forest disturbance, lichens are among the first living things to grow on fresh rock exposed after a landslide. Lichens can be very long-lived. The long life-span and slow and regular growth rate of some lichens can be used to date events, which is called lichenometry. This is not unlike how we can use tree rings, called dendrochronology, to date past weather events.

Some lichens are very susceptible to air pollution and have been used as effective biomonitors of air quality. Since lichens do not have deciduous leaves that fall off in the winter, their structure is exposed to air pollutants year-round causing the accumulation of pollutants. Because lichens do not possess roots, their primary source of most nutrients (and potential pollution) is the air, making clean air important for the organism.

In addition to being the primary diet for reindeer, lichens have had many human uses by many cultures. In some regions, lichens are a staple food or even a delicacy. Two obstacles are often encountered when eating lichens. First, lichens are generally indigestible to humans; and second, lichens usually contain mildly toxic secondary compounds that should be removed before eating. This is probably why they are not found in your grocer’s produce department. Lichens are also used as sources of dye, pH indicators, and traditional medicines.

Don’t let the lichens all around us in the Northwoods blur into the background. Take the time to enjoy the many shapes and colors of this fascinating organism.

For Field Notes, this is Scott Bowe from the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Kemp Natural Resources Station.